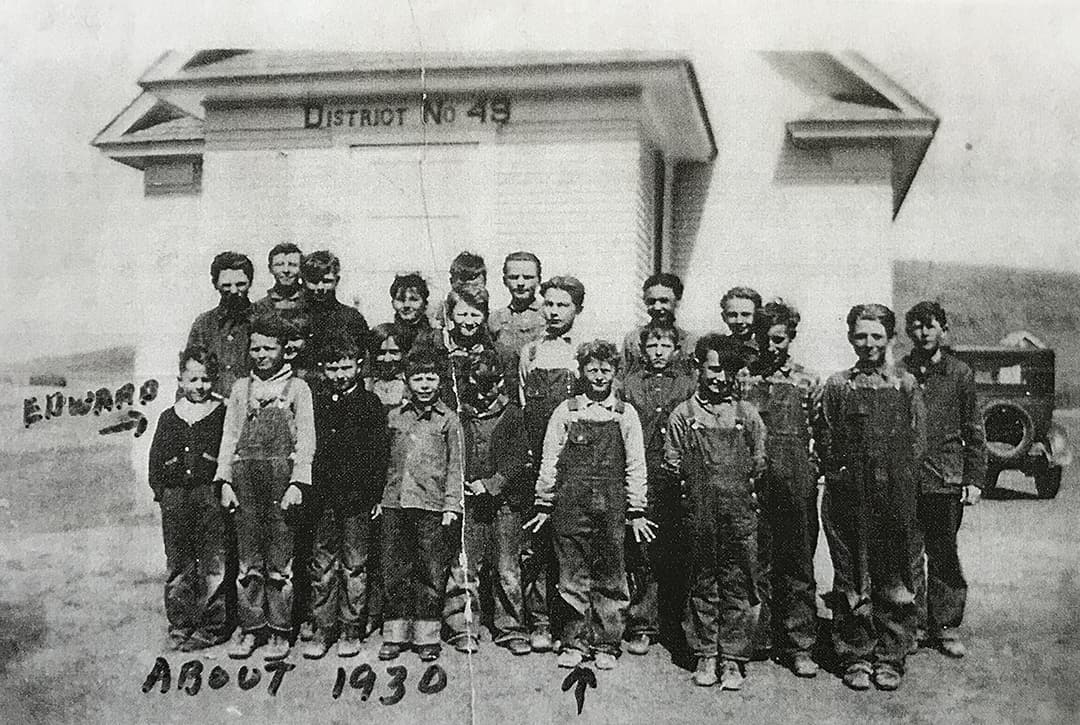

Being required to sit for an hour and a half at a school desk was tolerated only by the fact that after that time we were liberated by recess. A full 15 minutes of freedom, and then after another hour or so, a whole hour of relative freedom.

A part of that hour had to be allocated to lunch. My brother and I had a “store-bought” lunch pail, which included a thermos bottle that Mom would fill with cocoa in cold weather. Some students had gallon buckets with lids to serve as lunch pails. Prior to partaking of lunch, everyone had to wash their hands. In order to ration the amount of water used for hand-washing, one student would hold their hands, with a bar of soap, over the wash pan and another would pour a cup or so of water over them.

Our only supply of water was from the nearest farmstead, which was about a quarter of a mile down the road. Some of the older students would volunteer or be appointed to go there and bring back buckets of water to pour into the school crockery “water cooler.” One time a couple of water bearers were late in returning to school with water. Their excuse was “a swarm of bees was over the road and we didn’t want to get stung.” The weather was warm, and their “bee swarm” merely turned out to be heat waves shimmering above the road.

One teacher had a windup 78 rpm phonograph but with very few records, so she played “Away to Rio” nearly every day at lunch. I have heard that song only one time since, but I remember it very clearly.

Hattie B. was a very shy girl when she was enrolled in school. She would not eat her lunch. The only way she would eat was to place her in the entryway of the school and close the door, away from the eyes of others. Alma S. was in my grade, and about two or three times a month she came with a big yellow banana as part of her lunch—a quite unusual ingredient of a dust bowl lunch box. How I envied her. I entertained thoughts about asking for a bite but decided that this would not be very classy. Besides, her father was head of the school board, and he might take back the ball he had presented to us at the beginning of school. On some nice fall or spring days the teacher would have us take our lunch pails and sit on the bank next to the county road. The purpose was to see if any vehicle would drive by to provide us with a bit of entertainment. This very seldom happened.

There was not a bit of playground equipment around our school. This left considerable time for us to create our own entertainment. The farmstead that furnished the school water supply had two boys who attended our school. One day they came rolling a four-foot, probably 250-pound cast-iron flywheel from a corn sheller. While we did not have physics as a subject, we realized that a heavy, round object would roll down an inclined plane. The prairie-covered hill next to the school was quite high and steep, the perfect inclined plane. During noon recess, and with considerable group effort, we rolled the wheel to the hilltop. After catching our breaths, we let the wheel roll. It thundered down the hill, ripping through plum thickets and shooting across the road, before coming to a rest in the crick bottom. This effort was repeated several times, an excellent physical education project. I often wonder how lucky we were that an unfortunate motorist did not happen to be driving by at the wrong time or that the wheel did not hit the school, or another unwary student.

After savoring the success of launching the “Big Wheel,” we got to thinking it would be great if we could go down the hill by means of some wheeled vehicle. Here again the boys from the nearby farm came into the picture. Several of us scouted the farm’s junk pile and came up with four three-foot-diameter steel wheels with holes in their centers. These were brought to school, and again the coal hatchet came into use, chopping two saplings into axles, plus a couple others to connect the two axles. The two boys—Robert, a brawny eighth grader, and Jimmy, a smaller fifth grader—furnished us with nails and a hammer. The “vehicle” looked like it was ready to roll; the wheels on the wooden axles were held in place by big spikes driven through the axles. We pushed the vehicle to the top of the same hill that successfully launched the Big Wheel. It was agreed that the honor of the first ride should go to Robert. This was a fixed, nonsteerable vehicle. He sat on the back axle, and we gave him a little shove. The vehicle did not move, so Robert put his leg down to assist the movement. What happened next is a bit hard to tell.

Robert’s foot slipped, and his body fell into the spokes of the wheel. His arm got tangled in the spokes and drew his back across the bottom of the spike used to stabilize the interface of the wheel. We heard Robert scream, and fortunately several of us were alert to stop the vehicle. The tip of the spike tore Robert’s shirt on his back and gouged a cut over his shoulder blade. We slowly rotated the wheel to get Robert untangled. He went home to get bandaged up. That brought an end to our “freewheeling” times.

Fence staples are used to fasten barbed wire onto wooden posts. Common staples are about an inch in length, but there are staples that are about one-and-a-half-inches long for use where the wire may be subject to greater strain or where the posts are of softer wood. I don’t know just how this “sport” started, but someone of the older student group found that by taking one of these bigger staples, holding it between thumb and forefinger, and giving it a sidearm throw, the staple will stick in the wood if the distance to the target, such as the side of a building, was right. The force of the throw would affect the rotation of the staple. This is somewhat similar to the “throwing stars” of samurai warriors. There were quite a few staples thrown against the back of our schoolhouse, which did a certain amount of damage. The teacher inside, after hearing the strange sound of staples hitting the school, decided to investigate. Shortly thereafter we had to find other amusements.

Marbles was a game also played at recess time. Four holes were dug as corners of a square with one hole in the center. The game progressed, shooting marbles hole to hole, with the center hole being the last. As soon as a player’s marble hit the last hole, his marble became “poison,” and any player’s marble he could hit thereafter was “killed” and his to keep, although killed marbles were usually given back. One player brought a bunch of one-inch steel tractor ball bearings to school that were distributed among the players. These half-pound “marbles” caused the game to change more to a bowling tournament.

Ash trees were quite a common native tree. This was a desirable tree, not only as an excellent hardwood fuel for stoves; due to its supple strength, it served many other purposes around the farm. Many implement tongues, single trees, double trees, and neck yokes for horse-drawn equipment were made of ash, as were handles for different farm tools. When an ash tree was cut down, it didn’t take long for sprouts to shoot out from the base of the stump. These grew fast because of the extensive root system feeding them. In a few years there would be a ring of tree trunks around the remains of the original tree. As these sprouts grew to a three- or four-inch diameter with a height of perhaps 20 feet, they were quite flexible. There were a number of these second-growth trees near the school. We found that by climbing to about three-fourths of their height, we could get an entertaining ride by swaying our bodies in a wide arc, nearly touching the ground. We may not have had any playground equipment in the schoolyard, but who needs metal swings and slides when we could get suitable enjoyment from nearby trees?

The coal house behind the schoolhouse was also a repository for old, perhaps partly broken desks. When there was a light snow or a covering of sleet on the prairie hillside next to the school, we would go to the coal house and dismantle some of the desks. We would use the slick, curved seat backs as sleds. This would result in fast and wild uncontrolled rides with the edge of the “sled” occasionally catching on clumps of grass, causing it to come to a sudden stop with the rider continuing some distance over the snow, on his rear. The bell ending recess would bring the sledders indoors to stand with their backs toward the fired-up potbellied stove, resulting in steam rising from sodden overalls.

At one time in studying Indian life we cut a number of saplings, using our trusty coal-breaking hatchet. Using these saplings, we made a 10-foot-high tepee in the schoolyard. To cover the sides, we went to a nearby side hill, which was so steep it could not be mowed. There the grass accumulated so that armloads of it could be gathered without much effort. We covered the tepee with a thick layer of this grass. This even included a tunnel entrance. We were quite proud of our handiwork for several days until a high wind demolished our efforts.